Dallas Summer Musicals has been delighting audiences of all ages since the Roosevelt administration—from its first production of Blossom Time at the Fair Park Band Shell in 1941 to the closing of its 75th season in July at the Music Hall at Fair Park, a tour of Pippin. And while entertaining has been significant to its longevity, DSM President and Managing Director Michael Jenkins knows that there is another component that has contributed to the organization’s success, a principle that was introduced in the 1940s by Charles Meeker, the first managing director of Dallas Summer Musicals. Having worked alongside Meeker in the 1950s, Jenkins has never forgotten this principle:

Customer service is not everything; customer service is the only thing.

“Those words have carried with me through my entire career,” Jenkins says with pride. “People loved Meeker, as I did. He really understood the theater business and he gave me a great deal of opportunity that I would never have had.”

Jenkins developed an early interest in the world of musical theater, including investing in it. At 14 he was hired as an usher at the Music Hall. At 17, he was promoted to Meeker’s assistant. One day while in Meeker’s office he spotted an ad seeking investors for a new Broadway show. He had a hunch, so he spent the summer working three jobs to earn the $5,000 he needed to invest.

“That summer I worked from 6 a.m. to noon mowing lawns, then Meeker took me over to the Cotton Bowl to paint numbers on the seats and then I’d help out in his office.”

Impressed with her son’s perseverance, Jenkins’ mother loaned him the additional $2,800 he needed, when he fell short of his goal. The show, My Fair Lady, was a hit and so were the returns. With his earnings he bought his mother a new car, studied theater design at Baylor University in Waco and architecture under Ray Hoeiben.

That initiative has paid off for him and for Dallas Summer Musicals. Across seven decades, DSM has become the largest producer of live theater in the Southwest and a recipient of numerous honors, including some two-dozen Tony Awards due to Jenkins’ increasing role as a Broadway producer.

As DSM begins its 76th season this week with The Sound of Music, directed by three-time Tony Award winner Jack O’Brien, lets look back at some of its remarkable 75-year history through the eyes of Jenkins, who is remarkably only the third leader of the organization and has had some kind of involvement under the previous two.

The new tour of The Sound of Music opens Dallas Summer Musicals’ 76th season. Photo credit: Matthew Murphy

The callback that came 30 years later

In 1993 Jenkins was working in Europe when out of the blue he got a call from Don Spies, Board Chairman of Dallas Summer Musicals. “He told me Tom Hughes [DSM’s managing director from 1962 to 1993], had passed away and they were having some difficulties.” Spies asked Jenkins if he could return to Dallas immediately. Having stayed connected to the summer musicals as a member of the executive committee, Jenkins got back to Dallas as soon as he could.

On his return, he headed to the Music Hall office for a meeting with the board. Within minutes they told him that the union contracts had expired and there were no shows. “I’ll never forget my dear friend Charles Pistor saying to me, you’re the only one who knows how to do these shows, you have to do this.”

At the time Jenkins was managing 17 projects at Leisure and Recreational Concepts (LARC), a successful design and consulting firm for theme and waterparks he founded in 1971. When he realized the musicals might close, Jenkins stepped up. After all, this is where he’d gotten his first job.

“I said I’ll do it for one year.”

Now with two full-time careers to manage, he returned to the Music Hall office with assistant Wanda Crow and the two got to work, first working on some very unorganized files. When Jenkins discovered a box of complaint letters in a hall closet he vowed to answer each one.

At the time he was raising three small children alone and even with a busy travel schedule, he made it a priority to be home every evening. So he took six of the complaint letters home each night, read them, and then called the people who wrote them. One night, one of the women he called shared something that prompted him to make some changes to the areas surrounding the Music Hall.

She told Jenkins that she loved coming to the theater, but when her husband passed away, she was afraid to go alone. He thanked her and invited her to return. Then he got to work.

That first year he had the security guards dress in red jackets and he put them on horseback in the parking lots. “Red jackets so they could be seen, on horseback so they could see,” he says.

“And from my life at Six Flags, I put twinkle lights on the trees, and a guest relations attendant to open the door for her, what we call a blue jacket.” Jenkins also hung large lights in the parking lots. The woman did return and later she told Jenkins that she felt secure and thanked him for inviting her back.

What she didn’t know, Jenkins admits, was that there were actually two less security guards on the grounds than before, but instead of dark blue jackets, red jackets up high, where they could be seen. From then on ticket sales began to rise.

From the top

In the early 1940s the summer musicals were held at Fair Park’s Band Shell under the name Opera Under the Stars. The first show was an operetta inspired by Franz Schubert titled, Blossom Time. Crowds, dressed in their Sunday best, came out like the stars to enjoy the live musical productions. The season was a hit and so were the ones that followed.

“In those days people came out to see the show dressed up in long sleeves and ties, no matter how warm it got,” Jenkins fondly recalls.

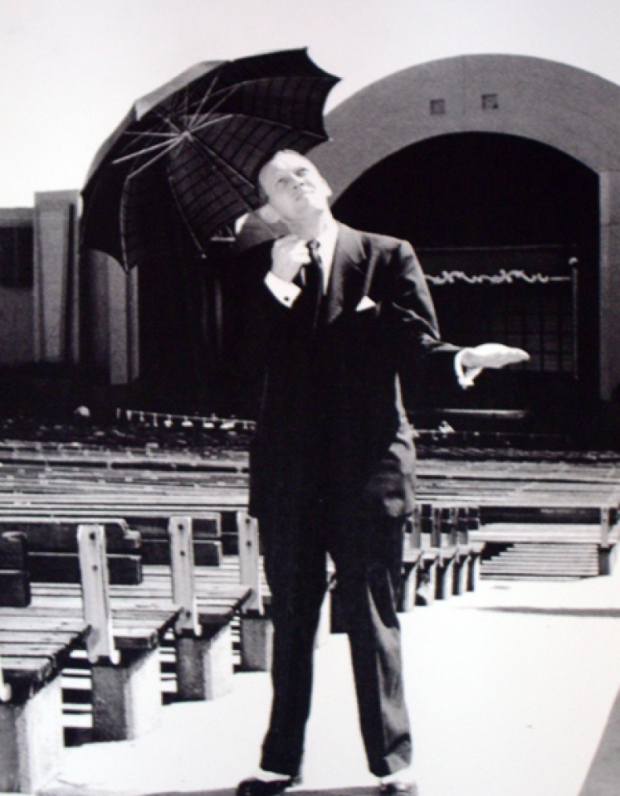

Realizing they were on to something, in 1944 the State Fair Association hired show business legend Charles Meeker to be the summer program’s first full-time Executive Director. A native of West Virginia and graduate of Southern Methodist University, Meeker had stayed in the area honing his show business skills. The summer musicals, now non-profit, also acquired a new name: Starlight Operettas.

Once on board, Meeker made technological changes to the Band Shell, including a moving platform system. And after persuading Mary Martin and her national tour of Annie Get Your Gun to come to town in 1947, it was clear, his “star system” was a success, attracting big names and setting box office records.

In 1951 Meeker moved the musicals into the newly air-conditioned Music Hall, making audiences happier and more comfortable. Because the shows were now inside, he was able to create further innovations to stage shows. Then the summer program was renamed again to The State Fair Musicals. The next year Meeker revived Porgy and Bess, George Gershwin’s opera featuring an all black cast, on the Music Hall stage. It was quite a risk in those days, but audiences loved it. The opera toured worldwide, and the performance put Dallas on the map as a real musical theater contender.

Throughout the 1950s Meeker brought big stars to the Music Hall, including Debbie Reynolds, Jose Ferrer, Gisele MacKenzie, Jeanette McDonald, Jack Benny and Judy Garland.

Then in 1961, he left State Fair Musicals to produce shows at the new Six Flags Over Texas. When he left, he took Jenkins with him.

“I was always interested in stage design, not in being an actor,” Jenkins says. “When Meeker left I was studying architecture and that took me to Six Flags with him.”

There, they created all the shows. Meeker trained the staff and created a program that had no employees, only hosts and hostesses and no customers, only guests. A program Jenkins would implement when he returned to Dallas Summer Musicals.

“It was very effective,” Jenkins says.

They called him Mr. Summer Musicals

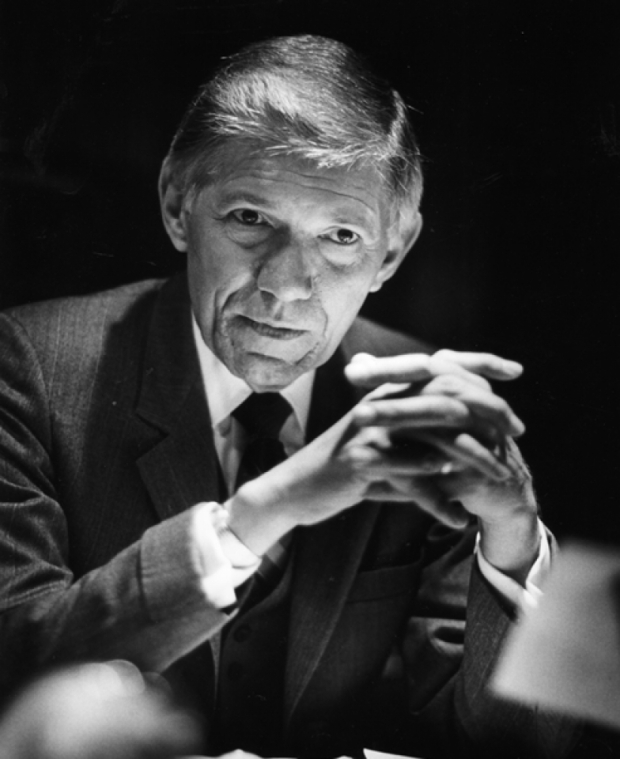

In 1955 Dallas native Tom Hughes headed for New York hoping to launch an acting career but when it was clear that was not going to happen, he returned to Dallas and began working as Meeker’s assistant at the State Fair Musicals. With the experience he had gained staging shows in high school, at Denton’s North Texas State University, and in Japan during the Korean War, Hughes knew he was back where he belonged.

As he learned the ropes, he was promoted to the Music Hall’s house manager and replaced Meeker as managing director when he left for Six Flags. The summer musicals split from the State Fair of Texas that year and became an independent non-profit organization, called Dallas Summer Musicals.

During the 1970’s, 80’s and 90’s, under Hughes’ leadership, several shows were produced by DSM and toured nationally, including Peter Pan starring Sandy Duncan, and Hello, Dolly! starring Carol Channing. Other stars that graced the Music Hall stage during his tenure were Pearl Bailey, Angela Landsbury, Rock Hudson, Carol Burnett, Gene Kelly and Tommy Tune.

“Tom loved the theater and loved to go to New York to audition the actors,” Jenkins recalls. “He would rent a place at the Plaza (Hotel), bring in a grand piano and sit for days auditioning them for new shows coming to Dallas.”

Throughout his 30 years with the Dallas Summer Musicals, Hughes developed into one of the most successful musical theater producers in the country.

Places everyone

“When I came back there were no shows and not to take anything away from Tommy, he produced several shows, but quite honestly there weren’t that many national tours at that time,” recalls Jenkins.

The price today to tour and to produce a show is very expensive. According to Jenkins, it costs between $12 and 15 million to put a show on Broadway and about $1 million per week to bring a show to Dallas from New York.

“There are 17 unions on Broadway,” he reports. “When you buy a ticket, when someone scans your ticket, and when someone hands you a playbill—you’ve already dealt with three of those unions and you’re not even to your seat.”

DSM stopped producing shows for a while but now they’re back in business: In 2014 it was The Little Mermaid (returning in 2016), in 2015 it was The King and I.

Major investments in Broadway shows are how Jenkins secures them for the Dallas market. As a producer, Jenkins’ 135th show on Broadway, An American in Paris, won four of the 12 Tonys it was nominated for. The tour will come to DSM in 2017.

When it comes to promoting DMS produced shows, Jenkins’ system, he says, is similar to the NFL football draft.

“I remember Jekyll and Hyde (1995) had gone to Tempe, Arizona but they didn’t really want it,” he chuckles. “But they were trying to fill their season so I called them up and they told me they wanted Cinderella and Singin’ in the Rain. So I said, ok I’ll give you Cinderella and Singin’ in the Rain in a future season if you take Jekyll and Hyde this season.”

“So that’s how I got that show and the same with Stage Door Charlie with Tommy Tune and several others, so if was kind of like the draft, and we eventually produced and toured Singin’ in the Rain, so that’s how it all got started.”

More hats

Jenkins’ role as DSM’s President and Managing Director doesn’t stop here. He also manages the Music Hall, the Majestic Theatre for the City of Dallas, and negotiates DSM-produced tours with others cities. He also oversees the DSM’s Academy of Performing Arts as well as some of the other community outreach programs associated with Dallas Summer Musicals, which includes bringing younger audiences to the Music Hall, many for the very first time.

“Bringing more than 2,000 children into the theatre every year, who have never seen a live theatre production is one of my greatest thrills.”

In 2014, Jenkins formed a partnership with Performing Arts Fort Worth, bringing the best of Broadway not only to Dallas but to Bass Performance Hall in Cowtown.

“Since Dallas can get shows for two weeks and Fort Worth for only one week, sometimes the one-week venues have to wait a year or two before they can get the bigger shows,” he says. “But by partnering with DSM, Fort Worth is able to get the bigger shows sooner. And from DSM’s point of view, we can market our shows together in the various publications for both cities. This is an extreme advantage.”

It’s become especially strategic since a third presenter of Broadway tours arrived in North Texas when the AT&T Performing Arts Center opened in 2009, and often bids against DSM for the tours.

Performing Arts Fort Worth President and CEO, Dione Kennedy, couldn’t agree more. Kennedy, who has known Jenkins for years, took over the reigns at Bass Hall in early 2009 after serving 18 years as President and CEO of Dayton, Ohio’s Victoria Theatre Association and the Arts Center Foundation. She and Jenkins are both members of the Broadway League as well as Tony Award voters.

“Right now it’s working really well,” Kennedy says. “The two organizations are saving money by pooling their marketing efforts. Presenting live musical theater is challenging when there is less product, as shows have become more expensive.”

“Michael is an incredible force who’s made a mark on the industry,” she adds. “He’s one of those people who help insure that there is new product coming along because creating new shows is critical on Broadway and Broadway on the road. I have complete trust and faith in him.”

Kennedy also believes that customer service is the only thing, and says that Fort Worth patrons are pleased with the partnership. “They love the idea of two non-profit organizations working together for the betterment of both.”

Another showman who has also collaborated with Jenkins on several business projects, and starred on Broadway and at Fair Park Music Hall, is former Olympic gymnast and Tony Award nominee, Cathy Rigby. She’s best known for her role as Peter Pan.

“He’s a pro and that is a given within the theater community,” Rigby says. “The shows he produces in Dallas have the same quality as the shows he produces on Broadway.”

The secret of his success

So how does he manage two very demanding and successful careers?

“When you surround yourself with better people you make your life easier,” says Jenkins. “I’ve seen situations where people would hire employees so they would always be on top, the king, so to speak. But I’ve never believed in that. I believe in hiring people much better than myself.”

While he is very involved with DSM’s operations, Jenkins gives his team freedom and flexibility to do their jobs, and says that 99 percent of the time they exceed all expectations. “I think that creates loyalty. So I am very proud of our team, our DSM family.”

And that kind of loyalty, which works both ways, includes the Music Hall ushers and a certain fountain on the lower level of Fair Park Music Hall.

A few years ago an usher told Jenkins that he was convinced his job would be the best job he was ever going to have. But Jenkins told him no, that he would go to college, get an education and a better job. The usher, knowing he could not afford it, was convinced it would never happen.

But the young man was given a scholarship from the coins dropped by patrons into the white, circular fountain in the Music Hall.

“We sent him to Oberlin College and he’s the youngest oboe player in the Memphis Symphony today. “It all started from that fountain, which yields between 8 and 13 thousand dollars a year.”

Two Americans in Paris

One night in 1959 Meeker had put Jenkins in charge of assisting legendary actor Maurice Chevalier, who was preparing for his show in his dressing room on a rainy Monday night. When Jenkins suggested he turn down the lights and close the doors of the Music Hall in preparation for the entertainer’s first number, Chevalier said “no,” that the people would be late making their way through the rain. “It’s the audience that is important, not me.” He repeated it, as he gently guided Jenkins to a seat by placing his right hand on his left shoulder. This was truly a defining moment for young Jenkins.

And then it happened again, nearly 39 years later when Jenkins and his wife Wendy were walking down the main street of Paris. It was a Monday evening and suddenly, it began to pour down rain. They quickly headed for cover under the red canopy of a café, and then ducked inside hoping to find a table.

Jenkins told the maître d’ they did not have a reservation but because it was raining they were hoping they could get a table. The maître d’ told the couple the only table he had open was a bankett, so they gladly took it. At the time, Wendy had an issue with back pain, so she sat on the outside of the booth facing Jenkins, and, happy to oblige his wife, he sat with his back against the wall. Suddenly Wendy said to her husband, “You’re not going to believe this, look over your right shoulder.” When he did, he saw a plaque on the wall that read: “This was the personal table of Maurice Chevalier.”

The 2015 tour of Pippin was shared by Dallas Summer Musicals and Performing Arts Fort Worth. Photo credit: Terry Shapiro

Some things never change

Something that continues to inspire Jenkins is seeing young children mesmerized by what they see on the stage. Perhaps they remind him of his own childhood, of attending musicals with his mother or riding the streetcar to Fair Park to watch the performers rehearse at the Band Shell from high atop the Ferris wheel.

And while new technologies in scenery and lighting are changing the way theater is presented and experienced—something that also inspires Jenkins—he still remains focused on the component that has been important throughout his entire career: taking care of his customers.

“Every time someone comes through the doors of the Music Hall, it’s like we are inviting them into our home and we want to treat them as good as we can. Sometimes we don’t get it right but we try to fix it. Without the customer we’re out of business.”

(This feature is also published on Theater Jones. Click here to view it there and to read more news about the Dallas performing arts scene.)